Complications of gastritis

Acute stress gastritis may lead to bleeding within a few days after an illness or injury, whereas bleeding tends to develop more slowly in the case of chronic erosive gastritis or radiation gastritis. If bleeding is mild and slow, people may have no symptoms or may notice only black stool (melena), caused by the black color of digested blood. If bleeding is more rapid, people may vomit blood or pass blood in their stool. Persistent bleeding can lead to symptoms of anemia, including fatigue, weakness, and light-headedness.

Gastritis can lead to stomach ulcers (gastric ulcers), which may cause the symptoms to get worse. If an ulcer goes through (perforates) the stomach wall, stomach contents may spill into the abdominal cavity, resulting in inflammation and usually infection of the lining of the abdominal cavity (peritonitis) and sudden worsening of pain.

Some complications of gastritis are slow to develop. The scarring and narrowing of the stomach outlet that can result from gastritis, especially from radiation gastritis and eosinophilic gastritis, can cause severe nausea and frequent vomiting.

In Ménétrier disease, fluid retention and swelling of the tissues (edema) may occur because of loss of protein from the inflamed stomach lining. About 10% of people with Ménétrier disease develop stomach cancer some years later.

Postgastrectomy gastritis and atrophic gastritis may cause symptoms of anemia, such as fatigue and weakness, because of decreased production of intrinsic factor (a protein that binds vitamin B12, allowing the B12 to be absorbed and used in the production of red blood cells).

A small percentage of people with atrophic gastritis develop metaplasia. In an even smaller percentage of people, metaplasia leads to stomach cancer.

Diagnosis of Gastritis

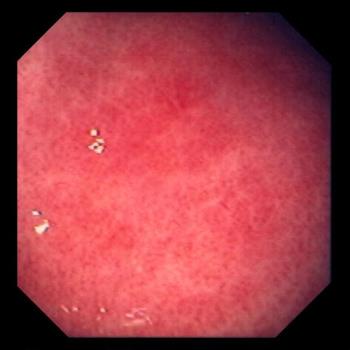

A doctor suspects gastritis when a person has upper abdominal discomfort, pain, or nausea. Tests usually are not needed. However, if the doctor is uncertain of the diagnosis, or if symptoms do not resolve with treatment, the doctor may do upper endoscopy. During upper endoscopy, a doctor uses an endoscope (a flexible viewing tube) to examine the stomach and some of the small intestine. If necessary, the doctor can do a biopsy (removal of a tissue sample for examination under a microscope) of the stomach lining.

Treatment of Gastritis

- Drugs that reduce acid production and antacids

- Sometimes antibiotics that treat H. pylori infection

- Treatments to stop bleeding

Regardless of the cause of gastritis, symptoms can be relieved by taking drugs that neutralize or reduce the production of stomach acid and by discontinuing drugs that cause symptoms.

Drugs for gastritis

For mild symptoms, taking antacids, which neutralize acid that has already been produced and released in the stomach, is often sufficient. Almost all antacids can be purchased without a doctor's prescription and are available in tablet or liquid form. Antacids include aluminum hydroxide (which can cause constipation), magnesium hydroxide (which can cause diarrhea), and calcium carbonate. Because antacids can interfere with the absorption of many different drugs, people who take other drugs should consult a pharmacist before taking antacids.

Acid-reducing drugs include histamine-2 (H2) blockers and proton pump inhibitors. H2 blockers are usually more effective than antacids in relieving symptoms, and many people find them far more convenient. Doctors most often prescribe proton pump inhibitors for gastritis associated with bleeding.

Doctors may prescribe sucralfate, which helps coat and heal the stomach and also prevents irritation.

When gastritis is caused by H. pylori infection, antibiotics are also prescribed.

Erosive gastritis

People with erosive gastritis must avoid taking drugs that irritate the stomach lining (such as NSAIDs). Some doctors prescribe proton pump inhibitors or misoprostol to help protect the stomach lining.

Acute stress gastritis

Most people with acute stress gastritis recover fully when the underlying illness, injury, or bleeding is controlled. However, 2% of people in intensive care units have heavy bleeding from acute stress gastritis, which can be fatal. Therefore, doctors try to prevent acute stress gastritis after a major illness, major injury, or severe burn. Drugs that reduce acid production are commonly given after surgery and to people in most intensive care units to prevent acute stress gastritis. These drugs are also used to treat any ulcers that form.

For people with heavy bleeding from acute stress gastritis, a wide variety of treatments have been used. Few of these treatments, however, improve the outcome. Bleeding points can be temporarily heat-sealed (cauterized) during an endoscopy, but bleeding often starts again if the underlying illness persists. If bleeding continues, the entire stomach may have to be removed as a lifesaving measure.

Other types of gastritis

There is no cure for postgastrectomy gastritis or atrophic gastritis. People with anemia resulting from decreased absorption of vitamin B12 that occurs with atrophic gastritis must take supplemental injections of the vitamin for the rest of their lives.

Corticosteroids or surgery may be needed to relieve a blocked stomach outlet caused by eosinophilic gastritis.

Removing part or all of the stomach may cure Ménétrier disease. There is no effective drug treatment.